Everything and Everyone wants in on open source these days — maybe you do too. This article is my attempt at articulating how I upstreamed my first kernel patch.

Let’s get started with a bit of background.

Background

I was writing a driver for work and I wanted to use i2c_transfer in a function to write some data on an I2C bus.

In brief, that function gets a handle to an I2C bus and executes the commands specified in msgs. Therefore, the struct i2c_msg struct should specify if the command is a read or a write.

There is indeed a flag that describes if the command is a read but there was no way to identify if it’s a write.

This is a pretty important API since I2C transactions are very common in embedded dev.

After digging through code that used i2c_transfer to write data, I learnt that not setting I2C_M_RD is the way to describe the transaction as a write. Here’s an example.

Since making this explicit is better than having this behavior undocumented, I decided to do that. I figured the best way of doing this was to update the description of I2C_M_RD.

This was not a very major change but the contribution workflow itself is not straightforward.

Let me elaborate on that with some theory of how the kernel development process works.

Theory

Unlike most FOSS projects that have the contributors submit their changes via PRs, the Linux kernel uses mail. A contributor has to mail their patches to the relevant maintainers and mailing lists who will review and comment on the patches.

If you don’t know what a patch is, it’s just a commit stored in a text file making it suitable for mail.

If the patch stands this scrutiny, it gets merged into the subsystem’s fork of the repo. During the merge window (which will be discussed later), these changes become part of mainline (Linus’ fork) and if the patch is a bug fix, it gets into stable and is backported if significant enough.

It’s important to note that patches should be of a reasonable quality if they are to get upstreamed (become part of mainline). Even high-profile incidents, like the scandal involving the University of Minnesota were not as successful as one might assume.

Now that we have the brief overview, let me go further in detail on the process.

The Kernel Development Process

This section will just be a very brief summary of the Linux development process. For further reading, please consult the official documentation.

The Kernel Release Cycle

The kernel uses a rolling development model. At the beginning of each development cycle, the merge window is opened. This is when maintainers forward feature patches to Linus. The bulk of major changes for a new development cycle will be merged during this time.

The merge window lasts for approximately two weeks. At the end of this time, Linus Torvalds will declare that the window is closed and release the first of the “rc” kernels. For the kernel destined to be v6.16 (current kernel as of the time of writing), this would be designated as v6.16-rc1. The -rc1 release is the signal that the time to merge new features has passed, and that the time to stabilize the next kernel has begun.

Over the next six to ten weeks, only bug fix patches should be submitted to the mainline. As fixes make their way into the mainline, the patch rate will slow over time. Linus releases new -rc kernels about once a week; a normal series will get up to somewhere between -rc6 and -rc9 before the kernel is considered to be sufficiently stable and the final release is made.

The most significant metric used to determine if the kernel is stable enough is the list of regressions from previous releases. At that point the whole process starts over again.

How Patches get into the Kernel

The kernel code base is logically broken down into subsystems: networking, memory management, drm, etc.

Most subsystems have designated maintainer(s), developer(s) who has/have the overall responsibility for the code within that subsystem.

These subsystem maintainers are the gatekeepers for the portion of the kernel they manage; they are the ones who will accept a patch for inclusion into the mainline kernel.

When the merge window opens, the top-level maintainers will ask Linus to “pull” the patches they have selected for merging from their repositories.

With that info in mind, let’s see how a patch is created and mailed.

Configuration

SMTP Configuration

Please refer to this link to setup an app password.

This password will be necessary when sending the mail with git send-email.

You could use a non Google SMTP server but I do not know how they work.

Git Configuration

Before starting, I would highly suggest you to configure your git username and email via

git config user.name "Your Name"

git config user.email "your.email@example.com"

You can check the config with

git config user.name # Prints user.name

git config user.email # Prints user.email

After you are setup with the configuration, clone Linus’ repo. You can do this via

git clone git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git # Linus' copy (mainline)

Creating the patch

Make the required changes and commit it, having the commit messages adhere to this format:

subsystem: brief summary of the change

Then add a blank line, followed by a detailed explanation of the change.

This is important because the first line will become the subject of the mail you will be sending.

You can check commits that have touched the file you want to understand what the commit should look like. This is done via:

git log -- <file-name>

See SubmittingPatches for more details.

When you are about to commit, add the -s flag to the command. This adds a Signed-off-by line at the end of the commit.

This is required as per Developer Certificate of Origin.

Assuming you have made n commits, create the patches by running

git format-patch HEAD~n

A single patch should contain one logical change.

After creating the patch(es), verify that it/they satisfies/satisfy the patch standards by running

${LINUX_BASE}/scripts/checkpatch.pl ${PATCH} # do this for each patch in case of a patch series

Note that your patch(es) should be as tested as thoroughly as possible if code was modified.

I won’t be covering that aspect in this article.

Mailing the patch

You need to figure out to whom the patch(es) need to be mailed to by running:

${LINUX_BASE}/scripts/get_maintainer.pl ${FILE_MODIFIED}

With that knowledge, It should be time to mail them.

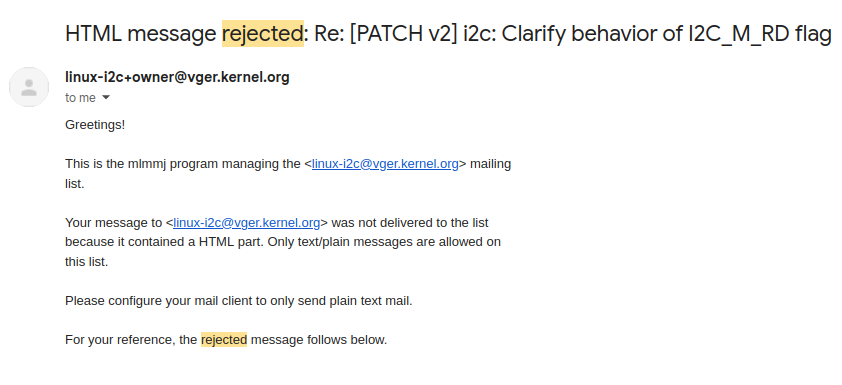

Keep in mind that the Linux Kernel Mailing Lists (lkml) expect you to mail in plaintext format which needs some setup. If you don’t do that, your mail will be rejected like this:

I wouldn’t recommend mailing patches via Gmail directly.

Git provides a dedicated command — git send-email — for sending emails in plain-text format.

You should use git send-email like this:

git send-email --to=<MAINTAINER-1> --to=<MAINTAINER-2> ... --cc=<LIST-1> ... patch/patches

This is the most basic command for mailing patches.

After a maintainer takes interest in your patch, they add it to Patchwork which is where you can track the progress of your patch.

Patchwork is a web-based patch tracking system that helps maintainers and contributors track the status of submitted patches, from review to acceptance and merging.

Here’s how my attempts went.

My attempts

Mailing a patch is just the beginning; You need to convince the maintainer that the patch is correct and necessary.

It’s a rather long process, and it’s quite common for you to get ghosted without warning if your patch isn’t proper which is what happened to me.

Attempt 1

This was my patch.

I threw in a second smaller patch because I believed that was just a free patch.

I sent it there because I thought that’s where newbies sent their patches. And I was very wrong.

I was thankfully redirected to linux-i2c@vger.kernel.org by one of the maintainers.

I then submitted the patch there and waited.

Attempt 2

Three months passed by and I realized that my patch would not be picked up.

So, It was time to go back to the drawing board. One of the first things I suspected was the subject of the patch.

The issue was “[PATCH] i2c: Update i2c_msg documentation to clarify write” was just too vague; That did not specify what exactly was changed. So, my solution was to change the title to “i2c: Clarify behavior of I2C_M_RD flag”. Here’s the submitted patch

This actually caught the attention of the maintainer and he was willing to accept it, if I signed with my legal name. I re-sent it almost immediately but then I made a really dumb mistake.

Attempt 3

The thing is I sent the patch with improper threading.

Without the correct reply-to, the patch will not show up in the thread making it hard to understand the conversation.

So, After a few months of waiting, I realized something was wrong and realized my mistake.

Here’s what the new command after adding reply-to looks like:

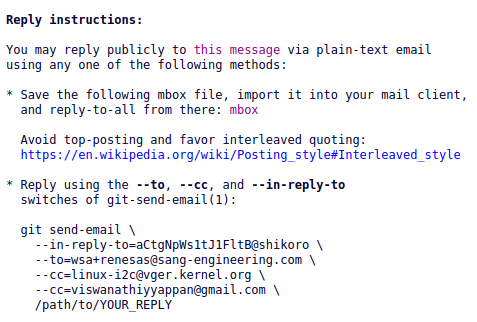

git send-email --in-reply-to=aCtgNpWs1tJ1FltB@shikoro --to=wsa+renesas@sang-engineering.com --cc=linux-i2c@vger.kernel.org --cc=viswanathiyyappan@gmail.com MY_REPLY

If you click the reply hyperlink below a message, it actually provides you with the command

This led me to create my penultimate patch.

I made a mistake missing the subject in the cover letter and corrected it here which was accepted.

Here is my final accepted patch. The commit id for this patch in upstream is c3ff7f06c787

Closing Remarks

This particular patch is very minor compared to a bug fix or a feature patch. But this was good enough for a first patch.

To be clear, It usually does not take months to get a patch (especially of this complexity) in. I just didn’t know what I was doing.

In a way, getting your first patch in is the hardest.

I hope this article has shed some light on the Linux contribution process and helped clarify things. Here are references for further reading:

The course explains the contribution process much better than this article.

I would also suggest participating in the Linux Kernel Mentorship Program (https://wiki.linuxfoundation.org/lkmp) if this was interesting to you.